I used to keep my book clean. Like most of college students, I looked to re-sell my book at the end of each semester to make room, both physically and financially, for new ones coming into the next term. Removable post-it notes to mark pages were always a must for a better resale price, and if I needed to write down anything, I made a reminder to myself to write in pencil, lightly and erasably. For a long time, the only thing in my pencil case were three pencils of three different types: one mechanical pencil for quick note, one HB pencil for annotation during my reading, and one 1B for underlining and drawing.

At college, we called the re-sale of books “flipping,” and I was among the most popular flippers around campus. In fact, I was able to finance my entire 7 semesters of reading materials simply through the “underground” trading of my old ones. As a business student, I understood what raises the value of a trade: the complete absence of the previous owners in the book. People come to buy used book as a financially effective option and, similar to every business, they want to get the most out of their deal. The criteria of value here happened to be the immaculateness of the book, or, in other words, how few signs of usage and previous ownership the book showed. How interesting it is.

Every book that parted my bookcase at the end of each semester looked immaculate, but I always ended up with a pile of notecards or post-its that were taken off the books before the sale. Annotation without texts, interpretation without evidence, ideas without ground. The books, then, were empty, both literally and figuratively, completely empty vessels by the time it reached the new owners.

It made me wonder every time I looked at my old books after the sale-prep process: how we you define “new” for a book? Was it the clean margin without any notes? Was it the unfolded corners? Was it the clean cover page, or was it the unmarked text?

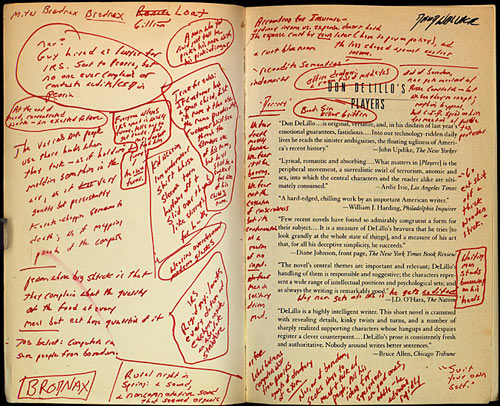

I used to borrow books from my professor for different classes and projects, and for my casual reading as well. Her books were always filled with notecards as well, but it was never clean. The margin would be covered with annotations, text underlined, passages linked together by carelessly drawn arrows. The notecards for her were simply added space when she ran out of room to write on her books. She usually had multiple copies of the same book, many of which were bought out of the love for the book, but the rest were to provide her with even more space to write. And she always wrote in ink on her book, blue ink, deep-ocean, like the perpetual ocean of thoughts that she left on the pages.

I was always very careful to note only in pencil in the books I borrowed and erase all of their traces before returning. I forgot once, however, and I received her email the day after. It went like this:

Hi Anh,

I was reading The Hour for today class, and I happened to see your notes on the passage…

Damn, I forgot to erase my notes in the book. No one wanted their thoughts to be tampered with, in the same way how every painter wanted a clean canvas before writing. Minimal requirement.

… and what brilliant ideas you had! Provocative, but truly brilliant.

Maybe it was not so bad. I had my emotional moments reading the books, and my annotations were the channel of release to myself.

… I am looking forward to discussing these ideas with you in class tomorrow.

Ok, now we have a conversation.

… All the best,

And all were good. I wondered why she did not get mad at me writing in a borrowed book. Financially speaking, it decreased the value of the book. Clean books always valued more in the flipping market. It could be considered trespassing into mental territory as well, right?

I reached out to her at the end of the following class about the notes and apologized for leaving my marks on her books before asking for my notecards back. She gave me back my notecards, of course, but brushed off my concerns over the annotations in pencil. It was a conversation between me and the text that she was glad to be part of. “It was like watching an artwork in the making. You do not get to see the blueprints all the time. I tell my students to feel free to write into my books whenever they borrowed one for reading. It put the book into good use,” she told me.

I spent the evening thinking about how to put a book into good use. What does it mean to have use a book well? Whenever I have a book, I always opened the first page and breathed in the woody smell of paper. It was something magical and exciting, the same as meeting riding your bike or swimming for the first time. It was never a feeling of possession to me, always a new horizon opened.

So I picked up a blue pen and wrote down, for the first time, into my book. I thought for a while, and wrote on the margin of a paragraph, “speak to the text, and anyone who may venture near.” I watched the blue ink sink deeper and deeper into the paper until it became a permanent mark and a part of the text itself. The book I was holding was no longer one of the millions of identical copies communicating the same pre-written text. It now communicated my text. The dried blue ink said there was a conversation that happened here.